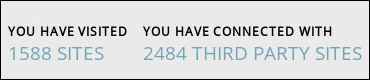

Lightbeam is a simple browser add-on for Firefox that lets you spy on web spies. More specifically, it reveals the full extent of all those behind-the-scenes connections websites make as you browse the internet. What’s the big deal with that? The results are positively creepy! Try it for yourself …

Install Lightbeam from its home page. It’ll only take a few seconds. Once its done, click on the Lightbeam icon up on the top right corner of Firefox to activate it.

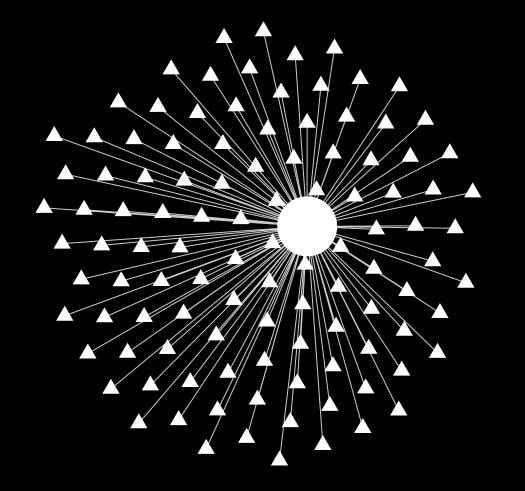

The next bit may may a little longer as Lightbeam races around mapping all the connections your browser has ever made. In my case, the result was the huge knotted muddle – a fraction of which you can see at the top of this post. A worldwide web indeed!

Each parent website is represented by a circle while its connections are shown as diamond-shaped satellites. Move your cursor over any of the graphics and a pop-up will detail the item’s web address. The display is interactive. Scroll the mouse wheel to zoom in and out, or click and drag a graphic to reposition it so you can examine more closely.

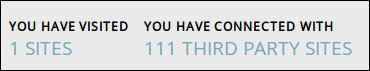

If that all looks overwhelming, start from scratch and see how the map builds up. Click Reset Data and choose OK to return to a blank screen. Now open a new tab with Ctrl-T or File / New Tab and browse to a website. I went to Startpage, “the world’s most private search engine”, then flipped back to the Lightbeam tab with this result:

Which is exactly what you’d expect. You visit a website, and there it is.

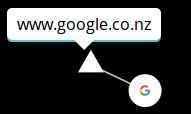

Now reset the data and try another site. This time I went to Google, with this result:

Again, no surprises there. I’m in New Zealand, so google.com has linked to its nearest affiliate, google.co.nz, via an unobtrusive third party connection (the diamond shape).

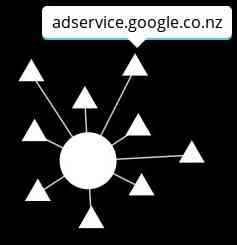

Reset the data once more and look at an actual website, as opposed to search site. I visited the international auction site eBay:

This is more disturbing. eBay, represented by the circle in the centre, has connected to nine other third party sites – three of which are Google or one of its online advertising affiliates. In short, even though I went to eBay, not Google, their ad servers are observing — and logging — my activity.

If you don’t find that particularly chilling, reset the data and visit the Wired tech news site.

Whoa! What the heck? Yep, typing in one single address has connected me to 111 third party sites!

Certainly, some of those links are Wired-related. Moving the cursor over each of the triangles pops up connections to places like CDNs – Content Delivery Networks that essentially speed up data delivery by acting like web caches, but many of them are to oddly named sites such as ir-na-amazon-adsystem.com, px.moatads.com and securepubads.g.doubleclick.net. Yes, they’re all advertising sites tracking your activity, watching what you click on and where you go next. Not a Facebook user? They’re still tracking you in case you ever become one. And if you are, even if you’re not signed in to Facebook, they’ll know where you’ve been and what you clicked on.

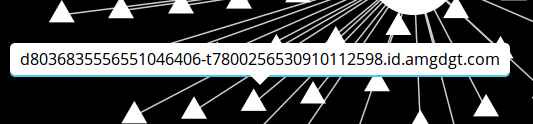

I also spotted this unusually named website:

Looks like I have my own personal tracker now too!

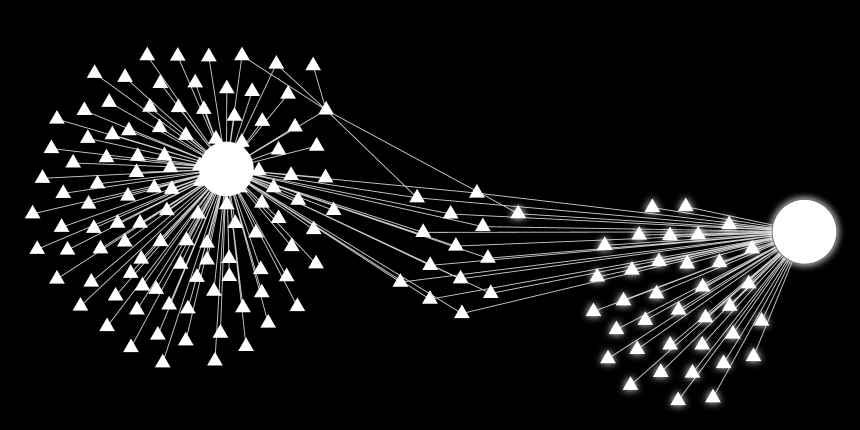

To continue the experiment, don’t clear the data this time, just visit another website. I chose the New York Times, with this result:

Notice how some of those third-party sites have common connections? Both Amazon and Google’s ad servers are following your activity. (I dragged the NYT to the right to make those connections clearer.)

In this way, companies you’ve never heard of track all your activity on line. They build up a picture of who you are, where you are, what you do, and what interests you. Ever looked for help on a personal issue — perhaps health related — something you haven’t even mentioned to your closest friend? It’ll be logged somewhere. Everything you search for, look at and link to is recorded. Some third party sites even note how long you spend looking at particular pages so they can rate your interest level. To say they probably know more about you than you know about yourself isn’t an exaggeration.

Not so anonymous

But it’s anonymous, right? They don’t know your name or where you live. Think again!

Back in 2006, AOL released 20 million search records for search engine developers to use as test data. The data, on 657,000 customers, was anonymised. IP addresses — which showed where the search requests came from — were replaced with numbers, but within days individuals had been identified just from their search terms. This piece, from the New York Times of August 2006, details how they identified one 62-year-old woman within hours.

Her searches are a catalog of intentions, curiosity, anxieties and quotidian questions. There was the day in May, for example, when she typed in “termites,” then “tea for good health” then “mature living,” all within a few hours.

Her queries mirror millions of those captured in AOL’s database, which reveal the concerns of expectant mothers, cancer patients, college students and music lovers. User No. 2178 searches for “foods to avoid when breast feeding.” No. 3482401 seeks guidance on “calorie counting.” No. 3483689 searches for the songs “Time After Time” and “Wind Beneath My Wings.”

At times, the searches appear to betray intimate emotions and personal dilemmas. No. 3505202 asks about “depression and medical leave.” No. 7268042 types “fear that spouse contemplating cheating.”

That was more than a decade ago, long before the social media boom. Considerably more data has been accumulated about users since then.

So what can you do about this and how can you reclaim a little internet privacy? How can you reduce the number of secret internet shoulder-surfers watching where you go and what you search for? I’ll tell you more in some upcoming posts.